Mobilizing Anger and Expertise: The Success of ACT UP

This essay was written for Prof. Kenney’s Political Science and Social Change class (SS112) at Minerva University in December of 2021.

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), founded in New York City in 1987 and eventually splitting in 1992, was a grassroots movement working to end the AIDS pandemic through direct action, treatment and advocacy, medical research, and changing public policy. ACT UP was "successful" in that in just fifteen years, it transformed AIDS and—in part—the society that surrounded it. Their accomplishments include designing a fast-track system to get sick people to experimental drugs (then forcing the FDA to adapt it), changing the CDC's definition of AIDS to include women, making needle exchange legal in NYC, and starting Housing Works (a service for homeless people with AIDS). The most astonishing part was that ACT UP had very few active members—at its height, only three to eight hundred people attended its meetings (Schulman, 2021). How did they do it? In this paper, I will explain how ACT UP was one of the most successful social movement groups of the late 1980-1990s due to its ability to unconventionally mobilize both anger and expertise for political, institutional, and social change.

The distributed structure and flexible leadership of ACT UP allowed members to “do their parallel but resonant activist work in whatever realms and ways that made most sense to them, with the people with whom they shared the most ‘affinity’ or agreement” (Schulman, 2021, ch. 1). This was both an advantage and disadvantage. An advantage of this distributed structure meant that ACT UP could act simultaneously in many different fields without needing full participation—if one subgroup within ACT UP was organizing a needle exchange program, and some people didn’t want to take part, they didn’t have to. This method allowed each ACT UP member to participate in a way that made sense to them, as long as it was under the umbrella of “direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” One disadvantage of this distributed structure is that the various functions and chapters of ACT UP didn’t have as much communication between each other, which may decrease the sense of international connection or purpose. For instance, a chapter of ACT UP started in Puerto Rico would be concerned mostly locally instead of imagining itself as part of a larger structure (Schulman, 2021, ch. 1). This would lead to ACT UP splitting into several different, smaller movements as time went on.

ACT UP needed to combat many stereotypes and assumptions about HIV/AIDS. Guided by Michel Foucault’s quote that “power and knowledge are inseparable,” ACT UP proved that “facts” about AIDS were biased with cultural assumptions. AIDS was first documented among 41 gay men in New York, and was frequently called a "gay disease" (Altman, 1981). This was dangerous since it implied that homosexuality had a biological component, or was itself a disease (Schulman, 2021). The religious right, bolstered by the recent election of Ronald Reagan (who refused to utter the word ‘AIDS’ in public in the early stages of the disease), seized the opportunity to further their homophobic antifeminist agenda (Reed, 2005). This pervasive ideology directly contributed to neglect of the gay community from government and the medical system. In addition, homophobia, racism, and sexism were all deadly social diseases that needed to be fought alongside AIDS (Reed, 2005). White males with access to healthcare were the first cases to be noticed and received disproportionately more media attention, to the extent where the disease was misrepresented as exclusively affecting white gay men. Though it was primarily an organization for gay identity, ACT UP positioned itself as an intersectional movement in fighting against racism and classism. ACT UP repurposed an American flag to say “the government continues to ignore the lives… of people with HIV infection because they are gay, black, Hispanic, or poor.” This poster appropriated the symbols of the flag and July 4 to grab attention of passerby and expose the inequity present in America.

ACT UP takes the instantly recognizable American flag and repurposes it to criticize the government’s response. Image taken from Reed (2005).

To fight against constructivist factors, ACT UP used its own. Losing a loved one to AIDS is a harrowing experience, and people’s sadness turned to anger at how the government and medical establishment ignored the deaths of thousands. ACT UP unified and mobilized its members’ personal anger towards the government and Big Pharma. They initiated emotional and political bonding through the creation of affinity groups. They also fought against harmful terminology. The term “AIDS victim” was common in the media, which implied passivity and disease lethality, so they encouraged the use of “people living with AIDS.” And instead of the term “risk groups,” ACT UP used the phrase “risk behaviors,” fighting stigma by putting the focus on behaviors (like unsafe sex) rather than innate characteristics (like homosexuality) (Reed, 2005, p. 198).

ACT UP faced substantial obstacles because it lobbied on behalf of highly stigmatized communities, including gay people, prostitutes, and IV drug users, while also fighting the public’s fear of contagion from an unknown disease. To combat the disease’s invisibility, members used the most visible methods possible, following a creed dictated by Ann Norhrop (one of ACT UP’s leaders): “Actions are always, always, always planned to be dramatic enough to capture public attention.” They wrapped the home of a senator in a giant yellow condom, laid siege to the FDA (“Hey, hey, FDA, how many people have you killed today?”), and dumped the ashes of people who had died of AIDS on the White House lawn (Specter, 2021). ACT UP’s use visual art, design, performance, and venue helped to display the diversity of expression while also grabbing public attention. An example of this is seen in the following image: flipping the pink triangle used during the Holocaust to denote homosexuals, and using it alongside the eye-catching slogan SILENCE = DEATH. Since it is easier to direct anger towards specific people rather than institutions, ACT UP used opponents’ faces in their campaigns. For instance, President Reagan’s face was put up with the slogan “He Kills Me,” which cleverly personalizes the threat and transforms it into collective action (Reed, 2005, p. 204).

ACT UP used this eye-catching slogan alongside a pink triangle. Image from Maggiano (2017).

Alongside ‘in-your-face’ tactics, ACT UP needed expertise to propose reasonable, doable, and winnable solutions to those in power, while also educating their members on nonviolent civil disobedience and media savviness (Schulman, 2021). This is where ACT UP used its substantial advantage: its diverse membership, including middle- and upper-class professionals who provided material and intellectual resources. This comprised artists, media professionals, and advertising copywriters who knew what would / wouldn’t work in American culture (Reed, 2005, p. 183). ACT UP members engaged in letter writing, petitioning, and lobbying, in addition to taking direct action (as had the Civil Rights movement) to force open a kind of negotiation more moderate forces had been unable to initiate and change public policy (Reed, 2005, p. 210).

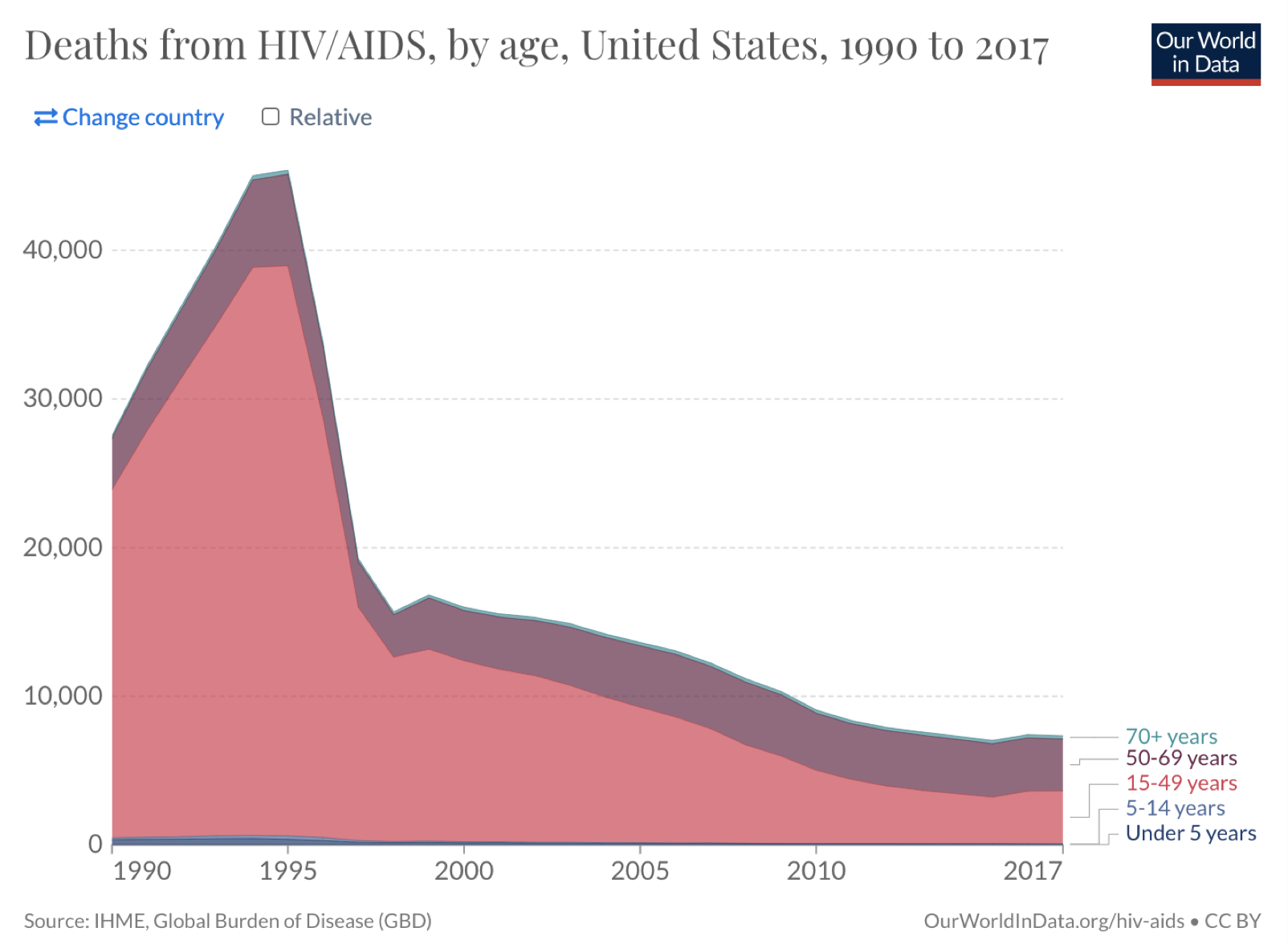

In the early stages of the movement, ACT UP needed to analyze the existing treatment for AIDS, which consisted only of a controversial drug called AZT that cost over $10,000 per year alongside minimal research and public education. The organization demanded that the FDA release life-saving drugs at affordable prices and invest in public education about the disease. Its first major action, Seize Control of the FDA, was successful due to its use of the Inside/Outside approach, in which some people in the organization had contacts with people in media or scientists in the government, while other people provided the street energy, organizing “impressive, innovative, visible street rebellions designed to pressure the institutional power” (Schulman, 2021, ch. 3). Frustrated with government inaction, renegade doctors and activists created the Community Research Initiative (CRI): a grassroots scientific and medical organization to study and test treatments separate from profit, looking only at what was best for the patients (Schulman, 2021, ch. 13). Also under ACT UP was The Science Club, which prepared a detailed assessment of N.I.H.-sponsored clinical trials and argued that sick people should have access to experimental drugs. They later successfully convinced the FDA to adapt this fast-track system, known as the “parallel track” (Specter, 2021). They also pioneered the idea of personalizing treatment using different medications, instead of the commonly-accepted ‘One-Pill-Cures-All’ approach, correctly believing that different treatments work better on different bodies (Schulman, 2021, Introduction). This helped with the development of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), a treatment that uses a combination of drugs to prevent the growth of the virus (“What Is Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)?”, 2014). The use of ART led to a dramatic decrease in AIDS deaths between 1995-1998.

A graph showing the deaths from AIDS in the United States over time. Notice in 1995, there is a dramatic reduction in deaths: this was due to the introduction of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART). Image from Roser and Ritchie (2018).

Another example of a gap ACT UP recognized was in education around the disease. The dominant model of medical expertise cared little about the opinions, experience, and cultural location of the client-patient. Thus, the information provided about AIDS was highly technical and hard to understand, especially by the communities that were most at-risk for the disease. ACT UP recognized this and, using its membership of education experts, advocated for education that was unprejudiced, not homophobic, frank, not euphemistic, and targeted in culturally-sensitive ways to minority communities, rather than blandly generic (Reed, 2005, p. 193). It partly achieved this through “teach-ins,” in which highly-informed people with AIDS were encouraged to be spokespeople because they were the experts (Schulman, 2021, Introduction). In these ways, ACT UP successfully identified problems, analyzed existing solutions, mobilized experts to design better solutions, and implemented them. ACT UP was one of the most successful movements of the 80s-90s through its ability to both mobilize and organize anger across a distributed structure, using both attention-grabbing, controversial actions, as well as the power of expertise to combat the AIDS crisis in America.

Bibliography

Altman, L. K. (1981, July 3). RARE CANCER SEEN IN 41 HOMOSEXUALS. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/03/us/rare-cancer-seen-in-41-homosexuals.html

Freeman, J., & Johnson, V. (1999). Waves of Protest: Social Movements Since the Sixties. Rowman & Littlefield.

Griggs, S., & Howarth, D. (2014). Post-structuralism, social movements and citizen politics. In H.-A. van der Heijden (Ed.), Handbook of Political Citizenship and Social Movements (pp. 279–307). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781781954690/9781781954690.00021.xml

Hubbard, J. (2012). United in Anger. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MrAzU79PBVM

Maggiano, C. C. (2017, September 8). Silence = Death. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/silence-death_b_59b29961e4b0d0c16bb52be3

Moser, R. (2015, July 31). Introduction to the Inside/Outside Strategy. Be Freedom. https://befreedom.co/introduction-to-the-insideoutside-strategy/

Reed, T. V. (2005). The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle (NED-New edition). University of Minnesota Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttv5w

Roser, M., & Ritchie, H. (2018, April 3). HIV / AIDS. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids

Schulman, S. (2021). Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. https://books.apple.com/us/book/let-the-record-show/id1530820667

Specter, M. (2021, June 4). How ACT UP Changed America. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/06/14/how-act-up-changed-america

What Is Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)? (2014, July 23). The AIDS InfoNet. http://aidsinfonet.org/fact_sheets/view/403