The Fight for Irish Language Rights in Northern Ireland

How a benign piece of equality legislation became a political roadblock—and how a grassroots movement is breaking barriers

In Belfast on January 16, the Irish language was spoken for the first time in a Northern Irish courtroom in over 300 years. Cuisle nic Liam, language rights coordinator with Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League), took the stand, announcing:

“Tráthnóna maith. Is mise Cuisle Nic Liam agus tá mé ag obair mar chomhordaitheoir cearta teanga le Conradh na Gaeilge.”

By speaking Irish in court, members of Conradh na Gaeilge consciously broke an Irish ban that had endured since 1737. Their efforts reflect centuries of grassroots efforts driving the fight for Irish language rights.

Though the recent passage of the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022 was celebrated as a landmark achievement in the media—offering official recognition for the Irish language, permitting its use in court, and pledging substantial funds for its preservation—its actual effects left many language rights advocates feeling disillusioned.

“What we were promised hasn’t been delivered,” Cuisle nic Liam told me over Zoom. She laments the fact that the Act’s impact remains stifled by political interference, underscoring the enduring influence of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in obstructing linguistic progress. In fact, nic Liam added, “it’s very much still illegal here to speak Irish.”

Looking at Northern Ireland’s tumultuous past, this is hardly surprising.

A (brief) history of Irish in Northern Ireland

For centuries, the British systematically marginalized the Irish people and suppressed their language. Prior to colonization, indigenous Irish was widely spoken throughout the island, with a writing system dating back to at least 400 AD.

In the 1600s, English statesman Oliver Cromwell punished the rebelling Irish people by passing a series of Penal Laws against Roman Catholics—who made up the vast majority of the population—all while taking their land and giving it to British settlers. It is estimated that between 15 and 50 percent of the native population perished during this conflict, which was worsened by an outbreak of bubonic plague.

Ireland’s population additionally plummeted during the Great Famine of the 1840s due to crop failures exacerbated by British colonial policies. During this time, the number of monoglot Irish speakers dropped from 800,000 to just 320,000.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a surge in Irish nationalism and calls for independence from British rule. During the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), the Irish Republican Army (IRA) engaged in guerrilla warfare against British forces. In response, the British deployed the Black and Tans, a paramilitary force notorious for its brutality and reprisal attacks against Irish civilians. By 1911, due to pressures from the Anglo-Irish administration, only 17,000 monoglot Irish speakers remained.

Proportion of respondents who said they had some ability in Irish in the 2021 Northern Ireland census.

To address the ‘Irish Question,’ the UK signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 which effectively partitioned Ireland into two parts: Northern Ireland (which it would hold on to, albeit with home rule) and the Republic of Ireland (which became a free state). The border aimed to separate the predominantly Protestant Unionists—who supported UK rule—in the north, while keeping predominantly Catholic nationalists in the south.

But just like the partition of India, this proved to be far from a perfect solution. A Unionist minority remained within the Republic of Ireland, just as a significant number of nationalists were left within Northern Ireland.

Under majority Unionist rule, Irish culture faced discrimination in Northern Ireland. Policies favored British identity and Protestantism at the expense of Irish language, customs, and Catholic traditions.

As put by former SDLP member Austin Currie: “Partition was used to try to cut us [Catholics] off from the rest of the Irish nation. Unionists did their best to stamp out our nationalism and, the educational system, to the extent it could organise it, was oriented to Britain and we were not even allowed to use names such as Séamus or Seán.”

These sectarian tensions culminated in The Troubles, a violent conflict between Catholic republicans and Protestant Unionists that killed over 3,000 people and injured over 36,000 between 1960 and 1998.

For over fifty years (1921-1972), the Northern Irish government excluded Irish from radio and television. And yet, despite numerous attempts to suppress it, Irish persisted. Republicans interned during The Troubles began learning the language—in what became known as the Jailtacht—as a means of communication and resistance. And following the Good Friday Agreement, the language has experienced a revival.

Today, the Irish language plays an important role in asserting Irish identity in Northern Ireland, even if only 12.4% of the country claims to speak it. As Cuisle nic Liam told me, “truly breaking free of a deeply entrenched colonial mindset will undoubtedly be challenging.”

A partisan battle

For centuries, organizations like Conradh na Gaeilge have been fighting to enshrine Irish language rights in the UK, hoping to pass an Irish Language Act akin to the successful 1993 Welsh Language Act.

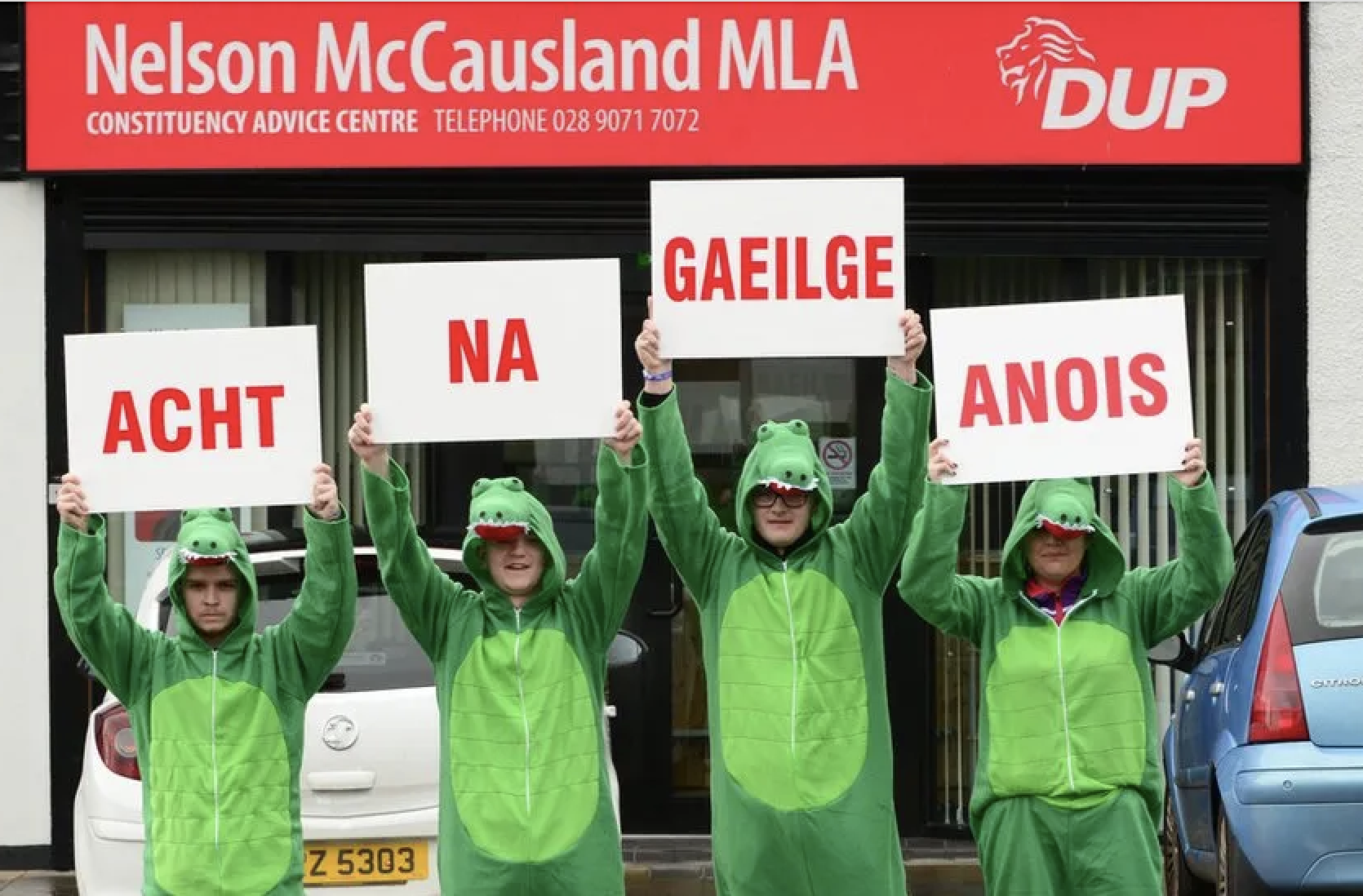

But they’ve faced significant challenges. Republican council members who dared to speak Irish in the courts were physically thrown out as late as the 1980s, and the language continues to be mocked by the Democratic Unionist Party to the present day. DUP MP Gregory Campbell coined the infamous taunt “Curry my yoghurt, can coca coalyer” in 2014, mocking an Irish phrase meaning “thank you, chairman.” Moreover, DUP leader Arlene Foster scorned a potential Irish Language Act, saying in 2017: “If you feed a crocodile, it will keep coming back for more.”

Members of Sinn Féin protest in front of DUP MLA Nelson McCausland's office in Belfast. Their signs read, “Irish Act now.”

On the flipside, Sinn Féin—the Irish republican party opposing the DUP—has been accused of “weaponizing” language rights to win political battles.

So what does this political back-and-forth mean for people on the ground in Northern Ireland? “I was raised in a protestant housing estate,” one Reddit user wrote in 2023. “I absolutely think that there should be equal recognition of the Irish language, it’s just the right thing to do… We all live in the same country, we need to stop making each others’ lives miserable and show a bit of respect, admittedly the unionist parties are behind in this aspect.”

Another user agreed. “It's unionism that has turned a benign piece of equality legislation into this political roadblock.”

Bilingual signage row

The implementation of bilingual English-Irish signage has been an enduring point of contention between the DUP and Sinn Féin. Currently, a mechanism exists for citizens to request bilingual signage for their street, but it is a long and arduous process.

An example of bilingual signage.

Installing bilingual signage in a Belfast leisure center was the focus of the January 16 tribunal. The Belfast City Council initially ruled in favor of the signage 12-6. However, a ‘call-in’ by the DUP meant that the council was required to seek ‘external legal advice’ on the matter. Lo and behold, this external legal advice ruled that the DUP had merit in calling in the decision, and that putting Irish alongside English on signage would negatively impact members of the community.

“Very rarely do these call-ins have merit,” Cuisle nic Liam told me. “So I submitted a freedom of information request to view this legal advice, but it was denied by the Information Commissioner... We were left completely in the dark.” And because a qualified majority of 80% is needed to uphold the original decision (the DUP occupies 25% of the committee), the bilingual signage proposal was effectively stalled.

The tribunal began when Conradh na Gaeilge appealed against a decision by the Information Commissioner not to reveal the legal advice. It was at this point that nic Liam and her colleagues decided to defy custom by speaking Irish in the courtroom. And—though the decision hasn’t been publicized yet—they won the appeal.

Yet some citizens aren’t convinced that bilingual signage is a good idea. “The cost of constantly cleaning paint off these Irish signs will be astronomical,” wrote one Reddit user six years ago.

“This is about [Sinn Féin] needing a win, and a standalone Irish Language Act is that win,” argued another.

The future of Irish language rights

The 2022 Identity and Language Act is “nowhere near what we need and have advocated for,” Cuisle nic Liam told me. “But it will lay a strong foundation for us.” Like many others in Northern Ireland, she is disappointed by the fact that both the DUP and Sinn Féin have turned Irish language rights into a quasi-pawn in a culture war.

“My optimism for the future doesn’t come from the political institutions,” she said. “I have no faith in the British or Irish governments, only in the community I am part of. Any advancement of the last 50 years has been a sole result of the community effort. I have no doubt that if this decision falls short, our community will have no problem in holding those responsible. In May of 2022 we had 20,000 people on the streets; it’s getting angrier and angrier,” she added, referring to an An Dream Dearg protest.

In the face of ongoing bureaucratic hurdles, preserving and promoting Irish in Northern Ireland can be viewed as a direct challenge to the historical marginalization of the indigenous language and its culture, particularly by the UK government. This postcolonial spirit echoes globally: similar struggles for linguistic recognition and revitalization include te reo Māori in New Zealand, Catalan in Spain, and the Sami languages of Scandinavia. Above all, these movements show us that language is not merely a tool for communication but the very essence of cultural identity and sovereignty. To deny minority speakers basic language rights is to deny them a fundamental aspect of their identity. It's an affront to their historical resilience and their right to exist and flourish within their own lands and societies. As one Northern Irishman wrote after the passing of the 2022 Act: “Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam.”

Meaning: “A country without a language is a country without a soul.”

Written for a journalism course at Minerva University, this explanatory journalistic piece takes a piece of recent news—Irish being spoken in Belfast courtrooms for the first time in 300 years—to examine the ongoing struggle for Irish language rights in Northern Ireland. It situates recent legal developments within historical context, and explores political dynamics as well as public sentiment. Its intent is to highlight the historical marginalization of the Irish language as well as shed light on the contemporary political landscape and the grassroots efforts advocating for linguistic equality. The audience likely includes individuals interested in Irish history, language rights, and Northern Irish politics. This piece could conceivably appear in a publication focusing on current affairs, politics, or cultural issues in Northern Ireland (such as Irish Legal News or the BBC) or in a broader context discussing minority language rights and cultural preservation.

References

BBC News. “‘Curry My Yoghurt’: Gregory Campbell, DUP, Barred from Speaking for Day.” November 4, 2014, sec. Northern Ireland. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-29895593.

BBC News. “Irish Language: Consultation on Olympia Leisure Centre Signs.” June 14, 2023, sec. Northern Ireland. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-65903127.

Belfast City Council. “Language Strategy.” Accessed January 28, 2024. https://www.belfastcity.gov.uk/documents/language-strategy-action-plan.

Carroll, Rory. “‘It Can’t Be Sidelined’: Bill Aims to Give Irish Official Status in Northern Ireland.” The Guardian, May 25, 2022, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/may/25/bill-irish-official-status-northern-ireland-language-government.

Conradh na Gaeilge. “An Lá Dearg 2022,” May 21, 2022. https://cnag.ie/en/news/1573-an-l%C3%A1-dearg-2022.html.

Corish, Patrick J. “The Cromwellian Conquest, 1649–53.” In A New History of Ireland: Early Modern Ireland 1534-1691, edited by T. W. Moody, F. X. Martin, and F. J. Byrne, 0. Oxford University Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199562527.003.0013.

Currie, Austin. “British-Irish Agreement Bill, 1999: Second Stage (Resumed).” Dáil Éireann debate, March 9, 1999. Éire. https://www.oireachtas.ie/ga/debates/debate/dail/1999-03-09/21.

Fenton, Siobhan. “How the Irish Language Became a Pawn in a Culture War.” New Statesman (blog), July 5, 2019. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2019/07/how-the-irish-language-became-a-pawn-in-a-culture-war.

Freedom of Information Act 2000, 2000 c.36 § (2000). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/36/section/42.

“Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Decision Notice,” December 7, 2022. Information Commissioner’s Office. https://ico.org.uk/media/action-weve-taken/decision-notices/2022/4023304/ic-174101-q3m4.pdf.

Gordon, Gareth. “Crocodiles, Alligators and the Irish Language.” BBC News, February 7, 2017, sec. Northern Ireland Election 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/election-northern-ireland-2017-38892198.

Hay, Marnie. Review of Review of Jailtacht: The Irish language, symbolic power and political violence in Northern Ireland, 1972-2008, Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost, by Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost. Studia Hibernica, no. 40 (2014): 239–41.

HISTORY. “How the Troubles Began in Northern Ireland,” August 2, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/the-troubles-northern-ireland.

Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act 2022, 2022 c. 45 § (2022). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/45/contents/enacted.

Lynch, Robert. The Partition of Ireland: 1918–1925. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139017619.

Maxwell, Nick. “Who Were the Black-and-Tans?” History Ireland, February 22, 2013. https://www.historyireland.com/who-were-the-black-and-tans/.

McClafferty. “Irish Language and Ulster Scots Bill Clears Final Hurdle in Parliament.” BBC News, October 26, 2022, sec. Northern Ireland. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-63402597.

O’Leary, Jennifer. “Why Is Irish Language Divisive Issue in Northern Ireland?” BBC News, December 17, 2014, sec. Northern Ireland. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-30517834.

Perry, Robert. “Revising Irish History: The Northern Ireland Conflict and the War of Ideas.” Journal of European Studies 40, no. 4 (December 1, 2010): 329–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047244110382170.

Simpson. “Thousands to March in Largest Irish Language Rally ‘in a Generation.’” The Irish News, May 21, 2022. https://www.irishnews.com/news/northernirelandnews/2022/05/21/news/thousands-to-march-in-largest-irish-language-rally-in-a-generation--2717553/.

Watson, Iarfhlaith, and Máire Nic Ghiolla Phádraig. “Is There an Educational Advantage to Speaking Irish? An Investigation of the Relationship between Education and Ability to Speak Irish,” September 2009. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJSL.2009.039.